The jaundiced take on that question is that if you don't know where you are going, you will never know when you arrive.

But for a writer it is different. It is good to know where your tale is going so that you can interweave plot threads and foreshadowings. Still there is a danger to that knowing. If you know, then a long-time reader might possibly second-guess the destination correctly. And that is the kiss of death to a novel.

For me as a reader, the fun of a novel is that the tale takes me by surprise. I think the tale is headed one place, and it spins around to another destination entirely. The antagonist is even worse than I imagined or one that I empathize with more than is comfortable. The protagonist has more facets than it appeared at the start.

How does an author take the reader by surprise? If only I had a sure-fire answer to that question, I would make a mint from the likes of Stephen King or Dean Koontz who have to surprise readers who are well-versed in all their tricks. But I have a hunch. And sometimes a hunch is all we have in life. And hope.

The hunch is that you can entertain readers with ironic twists and a protagonist who is a fish out of water in a well-known genre. The poet/scholar thrust into a profession that demands violent action. The individualist who is drafted into a militia that demands thoughtless obediance. The monster who finds himself having to fight monsters, in essence a wolf finding himself having to defend sheep.

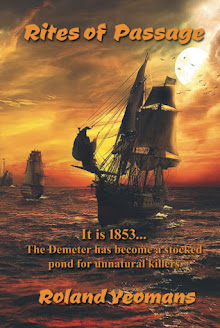

That hunch led to my creating the legendary undead Texas Ranger, Captain Samuel McCord. He is all of the above and more. He is also the answer to the question of some of my blogger friends who have asked how to write of a foreign locale in the past.

Part of the answer is that you find a modern parallel in today's headlines to the times of which you write. In the short story, THE DEVIL'S WIND, I used the parallel of our current struggle with Moslem extremists to link to the time of British Colonial India where Moslem extremists in the British Army killed thousands. At the beginning of my story, the uprising is just starting and McCord finds himself alone in a jail cell of a British outpost where every British citizen, civilian and soldier, is being murdered.

THE DEVIL’S WIND

“You will die, American. Slowly. Die as you starve to death in this cage.”

Your average man would have been scared. But I wasn’t a normal man. Hell, I wasn’t even a man. I was a monster.

I noticed the fluid movement within the reflections in the polished tiles beneath the Sepoy’s boots. Then, I got scared. Elu was hungry.

Elu? He was my Apache blood-brother. And his spirit was tied to mine. It had followed me all the way from Sonora to British-held India. His soul was held captive somehow by the ritual of our bonding by blood. I could see him sometimes in mirrors. And when he got hungry enough, he could reach out of them to feed on the spirits of others. One day I knew he would feed on mine. Was this the day?

I tried not to hear the screams of the dying outside the window of my jail cell and glared at the threatening Sepoy. “Debjit, you took an oath to honor that British uniform you’re wearing.”

Sneering at me from the other side of the iron bars, he turned to the other three Sepoys in the same Bengal Army uniform and spat on the gleaming tile floor. “An oath to infidels means nothing. Nothing!”

My fingers aching to wrap around his damn scrawny neck, I took off my Stetson and laid it gentle on the cot I was sitting on. “Your word either means something, no matter who you give it to, or you are nothing.”

“You dare lecture me, American?”

“Texican.”

“Fool is the better word. You are the one behind bars not me. I told you how the Colonel would reward you for rescuing his granddaughter from the Thuggees. And he did exactly what I said. He threw you into this prison for both England and China to fight over.”

“A man does what he thinks best -- or he’s not a man.”

His eyes became like a snake’s but without as much warmth. “Last month you saved my life. For Allah’s sake, I will not kill you. But neither will I free you.”

I nodded to his uniform. “Honor The Great Mystery by either not making promises or by performing them once you have.”

His face screwed up. “It is the British Army that lies. They would have us defile ourselves by tasting the grease of pigs when we use their bullets.”

I jerked my head to the shooting and dying screams outside my cell’s window. “I notice you boys don’t mind all that much now when you can kill helpless white women and children with those bullets.”

The youngest Sepoy jerked his rifle up. “You will die for that!”

“Hakesh, no! He wants to die quick.”

Debjit turned back to me and smiled wide. “Rather we will bring the great Colonel’s granddaughter here and kill her slow in front of this pig.”

I saw the dried-apricot face of my blood-brother within the reflections glimmering within the polished floor tiles under his boots, and I said softly, “Those are mighty sad last words.”

Debjit spat on those shiny tiles. “I laugh to hear a dead man make --”

A blackness, thick and cold, swept up from the polished stone. Debjit stiffened. Then, like a thing alive, the blackness swirled around him and his three companions. The living cloak of black mists tightened around the space where they stood. Screams, husky and muffled, fought to escape the darkness that boiled and rolled across the chamber.

I sighed. Although I couldn’t see inside the shadows, I knew what was going on. Knew all too well. I had seen clear too many times what was happening right then. The screaming became wetter, shriller. I heard whimpered pleas for mercy. There was thrashing, groaning, mewing as if from animals being skinned alive. Then, silence. Long, haunting moments of accusing silence. I looked at the darkness slowly flicker away like the light from dying embers.

The once polished floor was empty. Not one trace of the men who had been so full of comtempt and life just seconds before -- except for the steaming blood smeared across the tiles. There was the stench of burnt flesh. I forced the bile back down my throat. I smiled bitter. I would bet that the British obsession with spit and polish had never killed before.

From somewhere left of Hell, and seemingly from everywhere and nowhere in particular, came a hollow chuckle. I shivered. There had been a time when I thought I knew my blood-brother. That time had long since passed. Along with a lot of other things, like peace of mind and untroubled sleep.

I sighed, “You boys really shouldn’t have threatened Lucy, but that’s the sorry nature of human nature. It always goes one step too far. Elu will happily let me rot here in this cell. But he’s taken a fancy to the little princess.”

A touseled head of unruly black hair popped out from under my cot. “Elu? Captain Sam, who’s Elu?”

I jumped to my feet. “Lucy? How the .... How did you get under my cot?”

A dirt-smeared pixie scrambled to her booted feet in front of me. She was six, though she looked seven, and dressed in a tiny copy of a Bengal Lancer uniform. She slapped a canvas helmet on her head.

“No times for questions, Captain Sam. I got to get you to Grandpapa.”

I kneeled and looked underneath my cot. Son of a bitch. An opening into musty shadows. A hidden passage. Was this the reason the Colonel had been so insistent that I be put into this particular cell and no other? I caught faint echoes of shooting from down the tunnel. Fighting for time to think things through, I smiled up at Lucy.

Poor thing. She had been raised among rough men, been kidnapped by even rougher ones. She had heard things that no small child should. But I could use that to distract her and give me time to get a handle on my thoughts.

“What’s that thing on your head?”

She frowned. “I have you know this is the finest pith helmet ever made, came straight from London. A birthday present from Grandpapa.”

I smiled crooked. “A what?”

“A pith helmet. You know, pith.”

I pretended a frown.

She rolled her eyes. “Pith!”

“Why in tarnation would you want to slap it on your head after you did that into it?”

She stamped her right foot. “Not that! Pith!”

She spelled it slowly, “P-I-T-H!”

I fought a smile. “Oh, that.”

She snatched it off her long, wild hair and glared at it. “I do not think I shall ever wear this in quite the same way ever again.”

This time I did smile. “Do tell?”

She looked up and stiffened, sucking in a sharp breath of outrage. “Oh, Captain Sam, you and your bad jokes!”

Alarm widened her china blue eyes. “Oh, my! Grandpapa wanted me to give you this this the moment I came here.”

She hurriedly reached inside her tunic. She pulled out a folded piece of paper. She handed it to me. I sucked in a slow breath and took it. Standing a bit to the right so Elu could read it from inside the mirror over my shoulder, I looked down on the hastily written note.

Lucy peered outside my cell. “Ah, wherever are those Sepoy soldiers I heard from the tunnel?”

My face felt like it flinched. “They were -- invited to dinner.”

Lucy glared at me. “That’s another of your terrible jokes, is it not?”

There weren’t enough words in the dictionary to answer that right, so I just said nothing and read the Colonel’s note.

Captain McCord :

It would seem that the ill-conceived orders I was forced to obey have resulted in even worse consequences than I feared. It is a full

Mutiny. For hundreds of miles there are nothing but fanatical

Hindu and Moslem former soldiers of Her Majesty, armed with the

best weapons that the British Army has to offer.

My Lucy is doomed unless ....

There are strange and terrible tales told of you, sir. I can scarse

believe many of them. I know that in China you sank the British

flagship, Nemesis, and laid waste to the city of Ningbo to save a

British woman, Ann Noble, from being crucified by the Chinese.

Your own savages, Apaches I believe they are called, fear to step on

your shadow. Even your fellow Texas Rangers both fear and hate

you.

I do not know what to make of such tales. I only know that you

placed yourself in jeopardy to save my beloved granddaughter from

those Thuggee fanatics. My reason tells me that alone and unarmed,

you haven’t a prayer of saving yourself, much less Lucy. Yet, my

soul tells me that you are her one hope.

Please, Captain McCord, save my Lucy.

And ask her forgiveness for my telling her I would follow her. I

go now to join the ranks of my fathers, in whose presence I will not

feel shamed if you but get my Lucy to safety.

Colonel Lionel Wentworth.

I looked up, stared into my past, and whispered, “You got my word, Colonel.”

**********************

And no movie did the "Westerner Fish-Out-Of-Water" better than QUIGLY DOWN UNDER. And if I could pick anyone to play Sam McCord, it would be Tom Selleck.

But for a writer it is different. It is good to know where your tale is going so that you can interweave plot threads and foreshadowings. Still there is a danger to that knowing. If you know, then a long-time reader might possibly second-guess the destination correctly. And that is the kiss of death to a novel.

For me as a reader, the fun of a novel is that the tale takes me by surprise. I think the tale is headed one place, and it spins around to another destination entirely. The antagonist is even worse than I imagined or one that I empathize with more than is comfortable. The protagonist has more facets than it appeared at the start.

How does an author take the reader by surprise? If only I had a sure-fire answer to that question, I would make a mint from the likes of Stephen King or Dean Koontz who have to surprise readers who are well-versed in all their tricks. But I have a hunch. And sometimes a hunch is all we have in life. And hope.

The hunch is that you can entertain readers with ironic twists and a protagonist who is a fish out of water in a well-known genre. The poet/scholar thrust into a profession that demands violent action. The individualist who is drafted into a militia that demands thoughtless obediance. The monster who finds himself having to fight monsters, in essence a wolf finding himself having to defend sheep.

That hunch led to my creating the legendary undead Texas Ranger, Captain Samuel McCord. He is all of the above and more. He is also the answer to the question of some of my blogger friends who have asked how to write of a foreign locale in the past.

Part of the answer is that you find a modern parallel in today's headlines to the times of which you write. In the short story, THE DEVIL'S WIND, I used the parallel of our current struggle with Moslem extremists to link to the time of British Colonial India where Moslem extremists in the British Army killed thousands. At the beginning of my story, the uprising is just starting and McCord finds himself alone in a jail cell of a British outpost where every British citizen, civilian and soldier, is being murdered.

THE DEVIL’S WIND

“You will die, American. Slowly. Die as you starve to death in this cage.”

Your average man would have been scared. But I wasn’t a normal man. Hell, I wasn’t even a man. I was a monster.

I noticed the fluid movement within the reflections in the polished tiles beneath the Sepoy’s boots. Then, I got scared. Elu was hungry.

Elu? He was my Apache blood-brother. And his spirit was tied to mine. It had followed me all the way from Sonora to British-held India. His soul was held captive somehow by the ritual of our bonding by blood. I could see him sometimes in mirrors. And when he got hungry enough, he could reach out of them to feed on the spirits of others. One day I knew he would feed on mine. Was this the day?

I tried not to hear the screams of the dying outside the window of my jail cell and glared at the threatening Sepoy. “Debjit, you took an oath to honor that British uniform you’re wearing.”

Sneering at me from the other side of the iron bars, he turned to the other three Sepoys in the same Bengal Army uniform and spat on the gleaming tile floor. “An oath to infidels means nothing. Nothing!”

My fingers aching to wrap around his damn scrawny neck, I took off my Stetson and laid it gentle on the cot I was sitting on. “Your word either means something, no matter who you give it to, or you are nothing.”

“You dare lecture me, American?”

“Texican.”

“Fool is the better word. You are the one behind bars not me. I told you how the Colonel would reward you for rescuing his granddaughter from the Thuggees. And he did exactly what I said. He threw you into this prison for both England and China to fight over.”

“A man does what he thinks best -- or he’s not a man.”

His eyes became like a snake’s but without as much warmth. “Last month you saved my life. For Allah’s sake, I will not kill you. But neither will I free you.”

I nodded to his uniform. “Honor The Great Mystery by either not making promises or by performing them once you have.”

His face screwed up. “It is the British Army that lies. They would have us defile ourselves by tasting the grease of pigs when we use their bullets.”

I jerked my head to the shooting and dying screams outside my cell’s window. “I notice you boys don’t mind all that much now when you can kill helpless white women and children with those bullets.”

The youngest Sepoy jerked his rifle up. “You will die for that!”

“Hakesh, no! He wants to die quick.”

Debjit turned back to me and smiled wide. “Rather we will bring the great Colonel’s granddaughter here and kill her slow in front of this pig.”

I saw the dried-apricot face of my blood-brother within the reflections glimmering within the polished floor tiles under his boots, and I said softly, “Those are mighty sad last words.”

Debjit spat on those shiny tiles. “I laugh to hear a dead man make --”

A blackness, thick and cold, swept up from the polished stone. Debjit stiffened. Then, like a thing alive, the blackness swirled around him and his three companions. The living cloak of black mists tightened around the space where they stood. Screams, husky and muffled, fought to escape the darkness that boiled and rolled across the chamber.

I sighed. Although I couldn’t see inside the shadows, I knew what was going on. Knew all too well. I had seen clear too many times what was happening right then. The screaming became wetter, shriller. I heard whimpered pleas for mercy. There was thrashing, groaning, mewing as if from animals being skinned alive. Then, silence. Long, haunting moments of accusing silence. I looked at the darkness slowly flicker away like the light from dying embers.

The once polished floor was empty. Not one trace of the men who had been so full of comtempt and life just seconds before -- except for the steaming blood smeared across the tiles. There was the stench of burnt flesh. I forced the bile back down my throat. I smiled bitter. I would bet that the British obsession with spit and polish had never killed before.

From somewhere left of Hell, and seemingly from everywhere and nowhere in particular, came a hollow chuckle. I shivered. There had been a time when I thought I knew my blood-brother. That time had long since passed. Along with a lot of other things, like peace of mind and untroubled sleep.

I sighed, “You boys really shouldn’t have threatened Lucy, but that’s the sorry nature of human nature. It always goes one step too far. Elu will happily let me rot here in this cell. But he’s taken a fancy to the little princess.”

A touseled head of unruly black hair popped out from under my cot. “Elu? Captain Sam, who’s Elu?”

I jumped to my feet. “Lucy? How the .... How did you get under my cot?”

A dirt-smeared pixie scrambled to her booted feet in front of me. She was six, though she looked seven, and dressed in a tiny copy of a Bengal Lancer uniform. She slapped a canvas helmet on her head.

“No times for questions, Captain Sam. I got to get you to Grandpapa.”

I kneeled and looked underneath my cot. Son of a bitch. An opening into musty shadows. A hidden passage. Was this the reason the Colonel had been so insistent that I be put into this particular cell and no other? I caught faint echoes of shooting from down the tunnel. Fighting for time to think things through, I smiled up at Lucy.

Poor thing. She had been raised among rough men, been kidnapped by even rougher ones. She had heard things that no small child should. But I could use that to distract her and give me time to get a handle on my thoughts.

“What’s that thing on your head?”

She frowned. “I have you know this is the finest pith helmet ever made, came straight from London. A birthday present from Grandpapa.”

I smiled crooked. “A what?”

“A pith helmet. You know, pith.”

I pretended a frown.

She rolled her eyes. “Pith!”

“Why in tarnation would you want to slap it on your head after you did that into it?”

She stamped her right foot. “Not that! Pith!”

She spelled it slowly, “P-I-T-H!”

I fought a smile. “Oh, that.”

She snatched it off her long, wild hair and glared at it. “I do not think I shall ever wear this in quite the same way ever again.”

This time I did smile. “Do tell?”

She looked up and stiffened, sucking in a sharp breath of outrage. “Oh, Captain Sam, you and your bad jokes!”

Alarm widened her china blue eyes. “Oh, my! Grandpapa wanted me to give you this this the moment I came here.”

She hurriedly reached inside her tunic. She pulled out a folded piece of paper. She handed it to me. I sucked in a slow breath and took it. Standing a bit to the right so Elu could read it from inside the mirror over my shoulder, I looked down on the hastily written note.

Lucy peered outside my cell. “Ah, wherever are those Sepoy soldiers I heard from the tunnel?”

My face felt like it flinched. “They were -- invited to dinner.”

Lucy glared at me. “That’s another of your terrible jokes, is it not?”

There weren’t enough words in the dictionary to answer that right, so I just said nothing and read the Colonel’s note.

Captain McCord :

It would seem that the ill-conceived orders I was forced to obey have resulted in even worse consequences than I feared. It is a full

Mutiny. For hundreds of miles there are nothing but fanatical

Hindu and Moslem former soldiers of Her Majesty, armed with the

best weapons that the British Army has to offer.

My Lucy is doomed unless ....

There are strange and terrible tales told of you, sir. I can scarse

believe many of them. I know that in China you sank the British

flagship, Nemesis, and laid waste to the city of Ningbo to save a

British woman, Ann Noble, from being crucified by the Chinese.

Your own savages, Apaches I believe they are called, fear to step on

your shadow. Even your fellow Texas Rangers both fear and hate

you.

I do not know what to make of such tales. I only know that you

placed yourself in jeopardy to save my beloved granddaughter from

those Thuggee fanatics. My reason tells me that alone and unarmed,

you haven’t a prayer of saving yourself, much less Lucy. Yet, my

soul tells me that you are her one hope.

Please, Captain McCord, save my Lucy.

And ask her forgiveness for my telling her I would follow her. I

go now to join the ranks of my fathers, in whose presence I will not

feel shamed if you but get my Lucy to safety.

Colonel Lionel Wentworth.

I looked up, stared into my past, and whispered, “You got my word, Colonel.”

**********************

And no movie did the "Westerner Fish-Out-Of-Water" better than QUIGLY DOWN UNDER. And if I could pick anyone to play Sam McCord, it would be Tom Selleck.

No comments:

Post a Comment