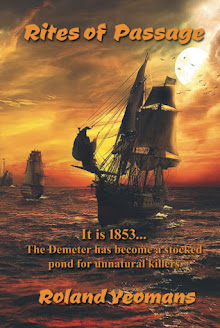

{Cover courtesy of the fabulous Leonora Roy.}

Question:

Which cover do you prefer?

This one or the one in the sidebar?

in a quote that launches the well-written, exhaustively researched biography, BLOOD AND CHAMPAGNE:

"Like the pen, the camera is as good as the man who uses it. It can be the extension of his mind and heart."

Blood and Champagne.

The term could be used on the yin yang of that most bothersome of aspects to our writing: pacing.

A good friend emailed me on a bit of a bother she was having with pacing on her WIP. It occurred to me that if she, as good a writer as she is, was having troubles with pacing, some of you might be having similar problems with it as well.

Both THE LEGEND OF VICTOR STANDISH and its latest sequel, THREE SPIRIT KNIGHT, have a lot of action in them. But like with pepper, action must be used wisely. But too much introspection or description is dangerously bland.

Pacing is all-important.

Think of the best jokes:

there is always a prep time that leads to the punch line. Without it, the punch is muted.

Where are your transitions in your novel? How does your MC get from here to there?

Reflection along the road, whether it be a physical one or a metaphysical one, is always a good way to pace -- and sow seeds for appreciation of the action to come.

The best monsters, the scariest moments in horror films are always the glimpses not the full shots.

In your novel, you show a terrorist place a suitcase under a table. You give a close-up of the timer: 60 seconds.

Two lovers sit at the table the terrorist just left. They talk about things important for the reader to know to understand the action of what is to come. But despite the flow of backstory, the reader stays keyed-up because between every paragraph you put one line:

40 seconds.

30 seconds.

15 seconds.

7 seconds.

No action. Only suspense. Then, BOOM!

It is a matter of instinct. It is, after all, your novel. Tell it your way. If your instincts bother you about a scene, listen to them. Ask if the pacing is off in some way. Too much build up? Not enough?

Each chapter is a three act play all its own. But with a difference -- each must end with a hook to link to the chapter following.

Each chapter must breathe.

No one inhales all the time. You have to exhale. So does the reader -- give her and him a chance to reflect.

Reading without reflecting is like eating without digesting.

Give your characters a moment to savor their victories or cringe from their defeats. Blows leave bruises. Show them. Let the readers see your characters limp from life's impacts.

Actions have consequences -- perhaps your instincts are telling you to paint the consequences more fully with an extra paragraph or scene or two.

If you want to slow the pace, write longer sentences -- when you want the reader to consciously think about what you're showing him.

This is true for paragraphs -- it will slow down the speed of the reader. But don't over-do this. Long, blockly paragraphs tire the reader.

Pace is the tempo at which a scene moves. You are the conductor of your own orchestra, playing your own composition.

You know the overall story you want to tell. Slow down to build tension and hit the reader with short, active sentences and paragraphs to tug the reader along for a wild ride.

Use shorter sentences when you want the reader to react, not to think -- as if he's taking part in the whirlwind action.

Then, too, there are hard words and soft words, both in sound and meaning.

You can choose either or both. Hard words are those that contain hard consonants or create small explosions of breath when pronounced: b-d-t-v- x-z, for example.

Soft letters let the breath escape slowly or create the sound in your throat or mouth: j-l-m-r-,s to name a few.

Though we don't read aloud usually, we still "hear" the words in our heads. So use those hard and soft words artfully to subconsciously build the mood you want.

Some words themselves create feeling:

He drew her head back / He yanked her head back.

Both sentences paint different pictures and create different feelings about the action.

Having a character flex his fingers hints at strength more than his stretching his hands would.

The overall pace of a novel needs to escalate as the story moves forward in order to keep the reader interested.

It has peaks and valleys along the way. Each peak must be higher than the ones before it, and each valley not as deep.

This gives the reader less time to catch his breath and little or no inclination to put the book down.

A good way to learn more about pace is by paying special attention to how published authors control pace in the novels you enjoy.

When a scene makes you bite your fingernails or clutch the edge of the chair, insert a slip of paper to mark the place so you can study the scene after you finish the book.

Analyze the scene this time, notice things the writer did that caught you up in what was happening as the pace sped up. How did the author stir your emotion or evoke a physical response?

Mastery of the fine art of pace comes with experience. Start getting it now with these few tricks and add and refine your pacing skills as you grow in your writing career.

I hope these thoughts helped you in some small way.

*) A word about my ending to GHOST OF A CHANCE and about my novella in general:

My ending is an analogy of sorts :

We authors do go throuh Hell, bringing our Main Character through the tribulations that end in a satisfying conclusion.

And also, we authors face the temptation of staying too long at the end, reluctant to leave those characters we have come to know and perhaps to care for deeply.

Best to leave the readers with laughter, a lingering melody, and a glimpse of love rewarded ...

but only a glimpse, the readers' minds will fill in the details much better than we ever could.

See? My ending, in fact of all of GHOST OF A CHANCE, was a lesson on how to write a little better.

Some lessons in how to do it. Sometimes in how NOT to do it. I wrote some of those chapters dead exhauted. Hopefully, knowing that, re-reading will be even more fun for those of you who do it.

Happy EVE of A-Z CHALLENGE, Roland

***

The love that shaped Ernest Hemingway's life for both good and ill :

That's one thing I had to learn to do - shorter sentences. It wasn't natural for me, but they do speed up a scene.

ReplyDeleteAlex:

ReplyDeleteAll of us have invisible bug-a-boo's that lurk unseen right before our eyes as we write. Always a good thing to have an editor you trust. Oh, Maxwell Perkins, where are you now? :-)

Each chapter must breathe -- awesome way to put it. My editor for Immaterial Evidence is pushing me to focus on how I pace scenes, and the advice has been invaluable. Regarding your covers...I'm really no help at all. I like them BOTH.

ReplyDeleteMilo:

ReplyDeleteYou're such an inventive writer that the thought my suggestions on pacing helped you a bit made my afternoon.

I wish you luck in the editing of IMMATERIAL EVIDENCE. Sometimes we get caught up in the flow of the story. It takes us longer to write a sequential scenes than it takes to read them, so we sometimes tend to rush through them too quickly, leaving the reader feeling breathless.

We need to read the flow of scenes to see if the narrative needs a moment of reflection or longer bouts of consequences of actions. :-)